RockyMtns Challenge

Date Started: 07/05/23 Date Finished: 08/17/23

|

| |

RockyMtns | ||

| 130mi (209km) | ||

| 9 Virtual Postcards | ||

| 10 Landmarks | ||

| ||

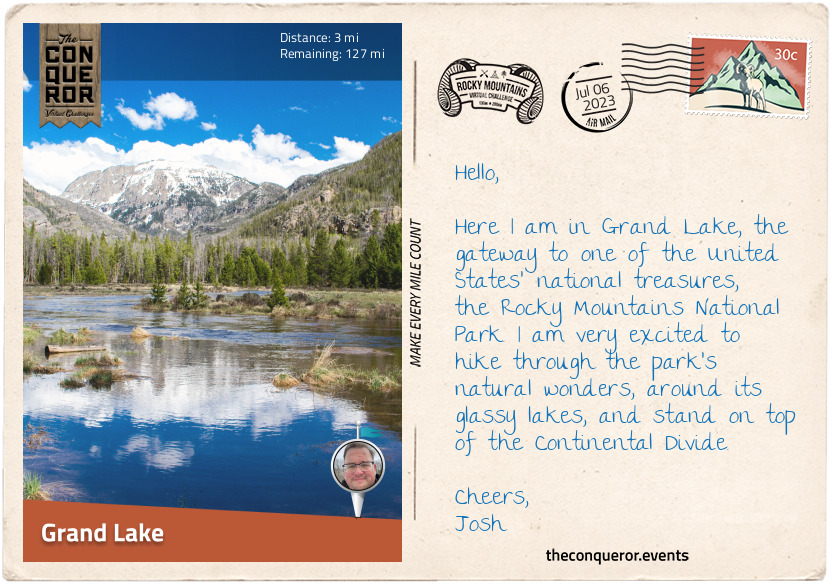

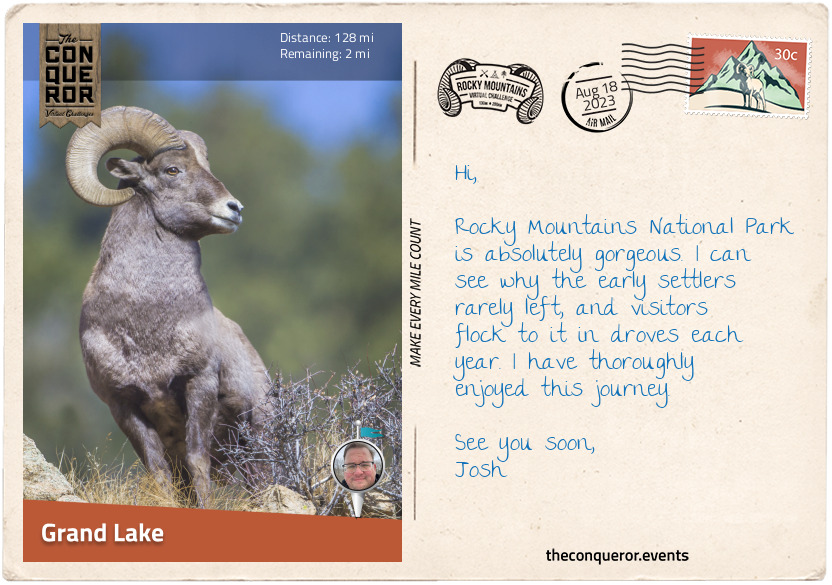

Grand Lake

Grand Lake

The Rocky Mountains is the most extensive mountain range on the North American continent, stretching 3,000 mi (4,800 km) from the northernmost of Canada to New Mexico, United States. Cresting the range is a series of spectacular national parks, including the Rocky Mountains National Park (RMNP).

Located within the state of Colorado, United States, the RMNP sits high on the Continental Divide containing an area of 415 mi2 (1,074 km2) across four ecosystems: montane, sub-alpine, alpine tundra, and riparian. Within its boundaries, more than 60 granite peaks over 12,000 ft (3,600m) rise into the sky, and over 150 lakes glisten down in the valleys and up in cirques.

Throughout the park, the wildlife and flora are in abundance. Elk and moose graze in wide-open meadows, pika and marmots scurry around, either filling their food stores or crashing a picnic party, and the symbol of RMNP, the bighorn sheep, may be watching from craggy cliffs. The park's tree species are magnificently diverse, from conifers, pines, and firs to willows, cottonwoods, and red river birch. In the spring and summer, low to the ground is a kaleidoscope of blossoming wildflowers, like the magenta Parry Primrose; Colorado's state flower, the Blue Columbine; or the striking scarlet Indian Paintbrush. It is no surprise that UNESCO designated the park a World Biosphere Reserve.

There is so much that could be written about this park that I would end up with an essay. So instead, I will start with my journey from one of the park's major gateways in the town of Grand Lake. Located in the southwest corner of RMNP, the town sits nicely on the north bank of Grand Lake with a great view of Shadow Mountain on the opposite side.

The first people to inhabit the area were the Native Americans thousands of years ago, including the Ute and Arapaho tribes. Many legends and superstitions abound around the lake, giving the site a mystical feel. One story tells of a time when an enemy tribe attacked the Ute tribe. Corralling the women and children onto a raft, they were pushed into the lake. Unfortunately, heavy winds and treacherous weather upturned the raft, and all aboard drowned. Now, when a mist descends upon the lake, the ghostly forms of those who perished appear, and their cries can be heard beneath the icy waters.

According to another legend, a supernatural buffalo roams the area, traveling to and from a specific hole in the ice, leaving extra large hoofprints every time the lake freezes. The Arapaho believe that the buffalo rose from the lake's depths like a spirit, earning the lake's moniker "Spirit Lake".

When settlers arrived in the early 1800s, they weren't concerned about the superstitious stories. They settled the region, built hunting lodges, and established an early form of local tourism. Later in the century, miners arrived, hoping to find gold or silver. Tourism returned to Grand Lake in the early 20th century, and the area has been a popular destination since.

Since Grand Lake is located on the west side of the RMNP and, farther away from major cities, it is less frequented than Estes Park in the east, so it is a quieter and more peaceful place.

I'll be heading north through valleys and meadows, over mountains, and around lakes. I look forward to breathing in the pine-scented air, feeling the breeze on my face, and spotting a few animals from afar. Let's go!

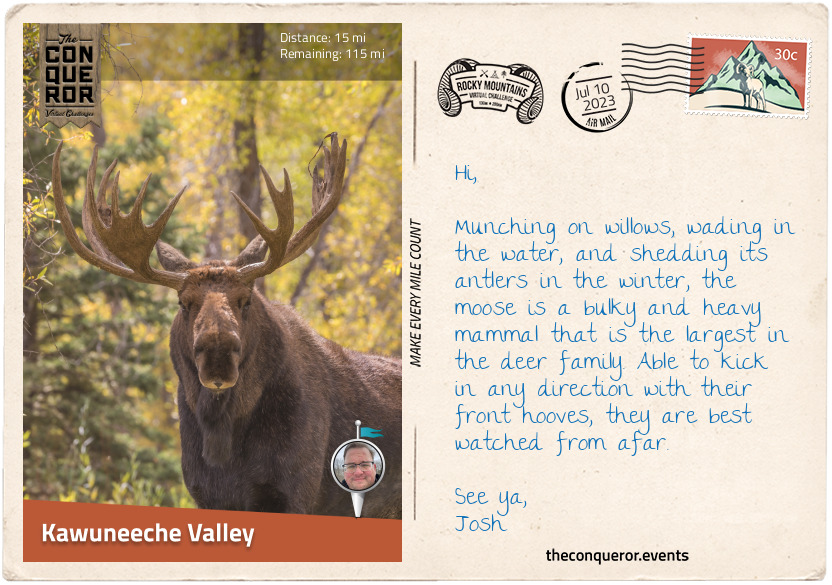

Kawuneeche Valley

Kawuneeche Valley

Having left Grand Lake, I passed the Grand Lake Cemetery. Dating back to 1875, it is the only active cemetery in a U.S. national park. The local historical society maintains a detailed record of those buried there, including the inseparable Harbison Sisters.

The sisters were early homesteaders, having moved into the area in 1896. Purchasing adjoining lots and building individual cabins, they set up a dairy ranch and supplied milk to local folk. When the park was established in 1915, the sisters refused to sell their ranch to the National Park Service (NPS). They lived there until 1938, when the property was incorporated into the park. Choosing to tend to the land and care for each other, the sisters never married. Contracting pneumonia, both sisters died only days apart, remaining devoted to one another forever.

I took the Tonahutu Creek Trail walking through a lodgepole pine forest to Big Meadows, a beautiful large meadow filled with wildflowers, tall grasses, and the Tonahatu Creek meandering through it. About halfway up on the trail's edge were two cabin ruins that used to belong to Sam Stone, a 19th century hay harvester and seller. One day he met a woman who convinced him to search for gold and abandoned his cabins, never returning.

Connecting with Timber Lake Trail, I continued through the forest until it opened to a long meadow at the southern end of Jackstraw Mountain. Skirting the mountain, I descended into the verdant Kawuneeche Valley, bordered by the many peaks of the Never Summer Mountains and the Colorado River passing through it.

I only had one mission here, and that was to spot moose in the area. The largest and heaviest species from the deer family, moose love to munch on the willows that are in abundance in the area, as well as aquatic plants and grasses. They are capable swimmers and can be seen wading around in the lakes. As fascinating as they are, moose tend to be unpredictable around humans. Since they can kick with their front hooves in any direction, they are best observed from afar.

I'll wander up to the Beaver Creek Picnic Area, settle down for lunch, and keep my eye out for these hefty mammals.

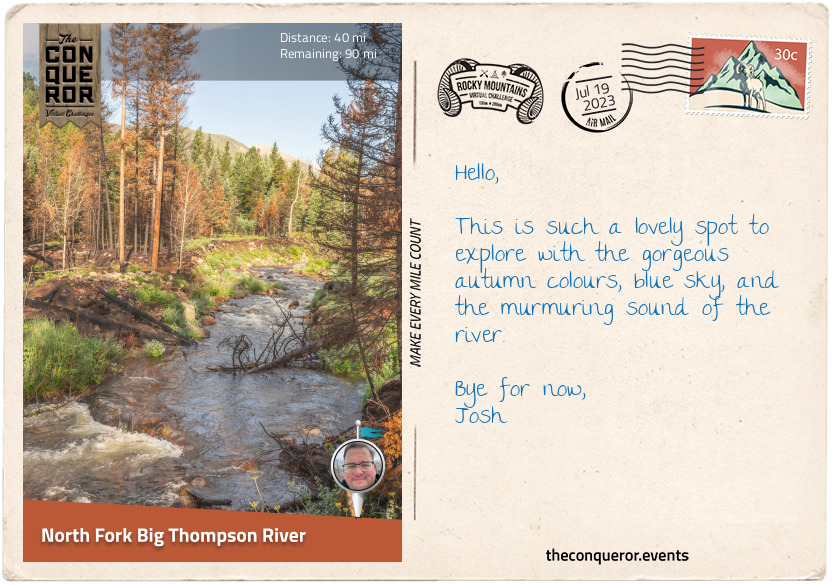

North Fork Big Thompson River

North Fork Big Thompson River

Good fortune was upon me with a great viewing of a handful of moose grazing in the valley. Packing up my gear, I pushed on north towards Lulu City. This former mining town came into existence when Joe Shipler discovered silver in the area in 1879. The town sprung up quickly, but it didn't last. Unfortunately, the silver was of low grade, and transportation costs were exorbitant. The town declined swiftly, and by 1885, it was abandoned except for Joe Shipler. He continued to live there for the next 30 years. When he left, his cabins and his nearby silver mine became part of the national park. The cabins were not maintained and are now in a state of decay, but I could imagine Joe stepping out his cabin door with a hot cup of coffee in hand, looking out onto Hart Ridge, flanking peaks, and the Colorado River. It was a sight to behold and understandable why he may have chosen to live there most of his life.

Passing by Long Draw Reservoir, a dam built in the 1920s that's great for fishing cutthroat trout, I connected to the Mummy Pass Trail and navigated the northern boundary of the national park. Through forest and long meadows, I stopped to take in the scenery at Mummy Pass, a cross between barren terrain, clumps of shrubs, and timberline. I skirted the southern flank of Fall Mountain, working my way down into a valley and then climbing back up to Storm Peaks Trail. The aspen trees here were beautiful with their bright green leaves and narrow silvery trunks. In autumn, the aspens turn to a brilliant yellow-gold colour before turning orange and striking red.

As I crossed the Stormy Peaks Pass, I started downhill to the junction of North Fork Trail. I set up camp at Lost Falls Campground and took a little wander along the North Fork Big Thompson River, quite a lengthy name. The walk was pleasant as I meandered beside the river through lovely woods on a gently climbing trail. After a mile or so, I returned to my camp, made myself something to eat, a hot cuppa, and sat back to enjoy the peaceful surroundings.

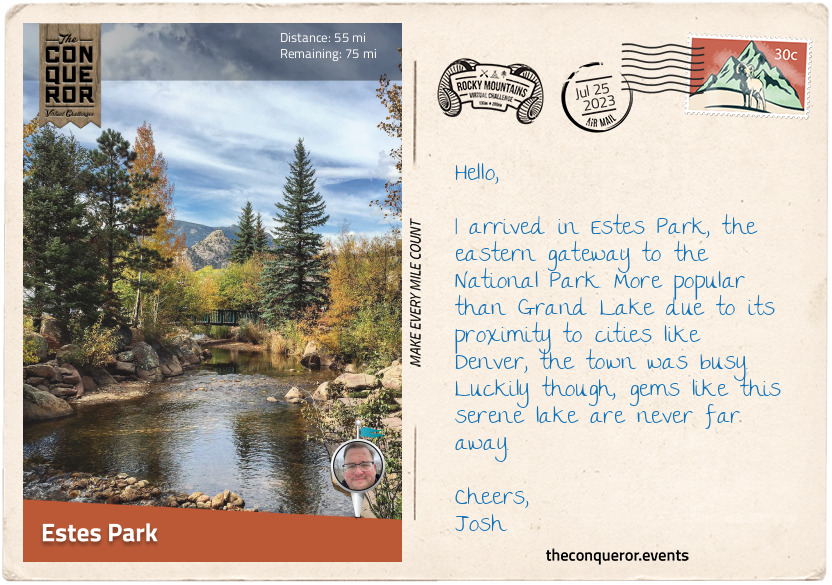

Estes Park

Estes Park

I began my day early, heading out on the North Fork Trail and hiking through dense forest. When I reached the junction with North Boundary Trail, I turned right and crossed the North Fork Big Thompson River. The trail steadily climbed around the side of a hill, and I peacefully forged onwards, travelling up and then down, crossing creeks and valleys, lost in my thoughts.

North Boundary Trail ended at Cow Creek, where the historical McGraw Ranch stands. Built in 1884, the ranch was used to raise cattle, then later converted into a guest ranch. When the National Park purchased the property, it initially planned to demolish it and let the land return to its natural state. However, the ranch was saved, fully restored, and repurposed into a research and learning centre. Although not open to the public, the ranch now houses researchers who spend weeks or months studying various aspects of the park's landscape and wildlife.

Swinging west, I followed Cow Creek Trail to Gem Creek Trail, then hiked south into Estes Park. The town is the very popular and very busy eastern gateway to the National Park. Estes Park was named after adventurer and miner Joel Estes. He was the first settler in the area, having moved into it with his family. Unfortunately, he found the place unsuitable for farming and left after only six years.

One of Estes Park's most important early 20th century residents was Enos Mills, endearingly referred to as the "Father of the Rocky Mountains National Park". In 1889, Enos had a chance meeting with naturalist John Muir, "Father of the National Parks", who advocated for the preservation of America's wilderness. Enos was a prolific writer capturing his adventures on paper, and John told him he could use his stories to educate others about the importance of nature. From then on, Enos dedicated his life to conservation activism, writing books and articles, and running lectures. He became the driving force behind the creation of the RMNP and never let up on it, even when the area was designated a forest reserve instead of a national park. He pressed on by writing thousands of letters. In 1915, President Woodrow Wilson officially created the RMNP, making it the tenth U.S. national park. Enos continued to live in Estes Park, writing and lecturing until his death.

In the centre of town is Lake Estes, a reservoir popular with anglers fishing for trout or water sport enthusiasts looking to kayak, paddleboard, or boat. I decided to stroll around the paved trail that skirted the lake and hoped to see elk or black bears, which are said to be common visitors to the lake's shores. Looking up at the sky, I hoped to see bald eagles. These fascinating birds of prey with their white head, yellow beak, and dark brown plumage have been the United States' national emblem since 1782, and the Native Americans revered them for their strength, seeing them as a symbol of courage, wisdom, and leadership.

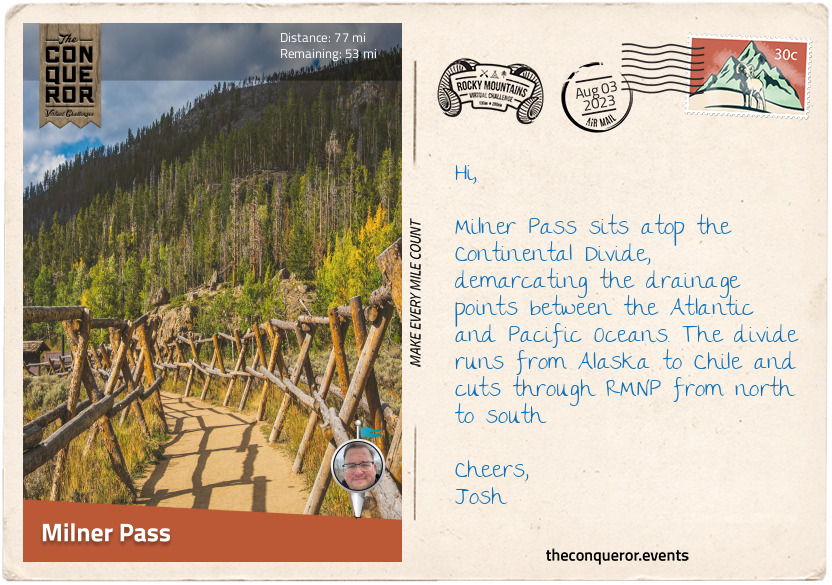

Milner Pass

Milner Pass

Heading west on Fall River Road, I passed the very rocky Castle Mountain with its castle-like peaks. An isolated mountain, I took a short side trip to hike up to the top. Although there was no specific trail, I crossed many dirt roads and used them to navigate to the top. From the summit, I had fabulous views over Estes Park and the lake. But I did not stay long, as mountain lions were known to hover around this rocky area.

Walking back to my route, I passed several lodgings that I could only imagine being fully booked at the height of the season. When I reached the base of Bighorn Mountain, the road forked, and I veered onto Endovalley Road. The Sheep Lakes here are known to be a grazing site for bighorn sheep. They descend from the Mummy range during late spring to early summer to nourish themselves with nutrients not found at a higher elevation.

A short distance later, I took another short side trip to the very pretty Horseshoe Falls. Not particularly tall, I still enjoyed the rushing sound of the water as I watched it tumble over several boulders into the creek below.

Less than 2mi (3.2km) later, I came across Chasm Falls plunging through a narrow granite gap. As I rested, taking in the scent of the ponderosa pines, I watched a couple of American dippers frolicking in the river. These small, stocky, dark grey birds are so-called because of their bobbing and dipping movements. I watched them dive underwater and walk along the bottom, foraging for food. They tend to be found around fast-moving streams, like here at Chasm Falls.

Chasm Falls is located off the Old Fall River Road (aka 'The Old Road'), a narrow seasonal, one-way, gravel road. About 9mi (14.45km) long, the road was opened in 1920, and it was the first car road that led into the high country of RMNP, reaching an elevation of 11,700ft (3,566m). Without guard rails and at dizzying heights, 'The Old Road' follows a series of tight switchbacks, climbing from Endovalley to spectacular views and ending at the Alpine Visitor Centre. Keeping my eyes peeled, I spotted elk grazing in Willow Park, although I was still hoping to spot a cheeky little marmot.

At the visitor centre, I connected with Trail Ridge Road, the highest continuous road in the United States. The road boasts an elevation of 12,183ft (3,713m) and incredible panoramic views of mountain ranges hundreds of miles away. Wildlife can often be sighted, and in some areas, walls of snow survive throughout the year.

My objective on this road was to reach Milner Pass so I could stand on top of the Continental Divide, the drainage divide that separates the Pacific Ocean's watershed from the Atlantic Ocean's. This invisible divide traverses America from the Baring Sea, Alaska, to the Strait of Magellan, Chile.

The Pass was right next to Poudre Lake, an ideal place to stop for lunch and a rest before I turned off onto Ute Trail.

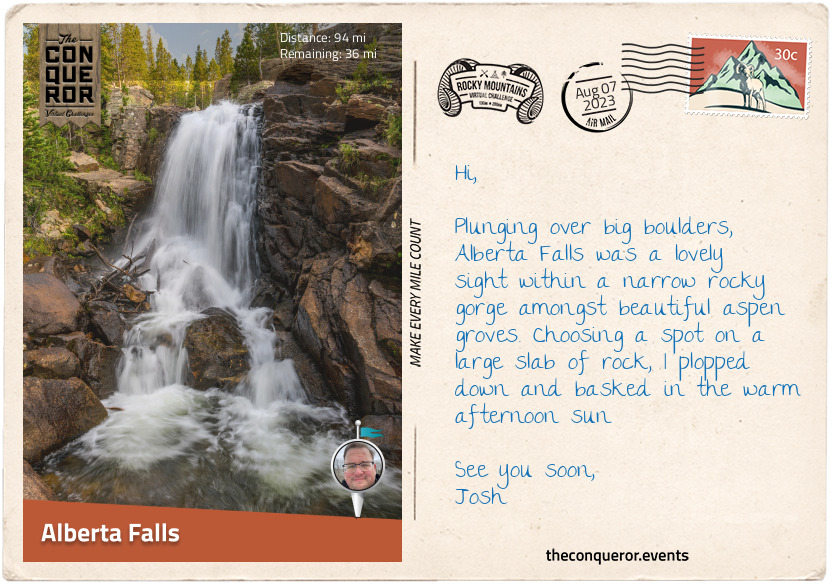

Alberta Falls

Alberta Falls

From Milner Pass, I began the Continental Divide traverse through the park. After a short stint on Ute Trail, I entered the backcountry through rugged terrain and no defined route. I hiked up to the ridge of the Front Range, with my first target to reach the summit of Mount Ida. The hike was above the treelines on a barren and rocky landscape with very steep sections. Down below in the valley were the remote Azure Lake and Inkwell Lake. I contemplated climbing down to the lakes, but the elevation drop of nearly 1000ft (300m) with lots of scrambling was a great deterrent. So, I just enjoyed it from the top.

I hiked along the ridgeline, descending to the glassy Haynach Lakes. Following the trail through the forest, I began another ascent at Tonahutu Creek Trail. I continued to Flattop Mountain, where my Divide traverse ended as it continued south while I turned left. As I gazed north of Hallett Peak, I glimpsed a small cirque glacier known as Tyndall Glacier. It was named after John Tyndall, an Irish scientist and alpine mountaineer. John was known as the first person to ascend Switzerland's Weisshorn Peak in the Alps. He also identified "carbon dioxide as a heat-trapping greenhouse gas".

Taking the Flattop Mountain Trail, I traversed a barren landscape, passing gnarled krummholz, aspen trees, and boulders. I ended up at Bear Lake. The region here is another significant entry point from the east, with many trails to tackle in all directions to explore splendid glacial lakes and picturesque forests. The quickest one to do, though, was the half-mile (1km) loop trail around Bear Lake, tucked within a treeline of spruce, aspen, and lodgepole pine.

Eager to see another waterfall, I connected to Glacier Gorge Trail, where the hike through the woods was easy and reasonably flat. The trail was well-maintained, and as the sun streamed through the trees, I walked beside Glacier Creek, listening to its burbling flow. I veered off the main trail through a narrow gorge arriving shortly after at Alberta Falls. Noisy and thundering, the cascade, set amongst aspen trees, plunged over massive boulders into Glacier Creek.

Alberta Falls was named after Abner Sprague's wife. Abner was one of the original settlers in the Estes Park area. In the late 1800s, Abner built a guest lodge and several other properties in the immediate area. From the mid-20th century, the National Park Service began purchasing all commercial developments within RMNP, including the Sprague properties, demolishing them, and returning most of the park to its original state.

Abner Sprague was a keen outdoorsman who loved Estes Valley. He was instrumental in developing the national park. Once the national park was signed into law, Abner went down in history as the first person to pay an entrance fee.

Taking a break to rehydrate and snack, I watched a blue-tailed Steller's Jay jumping on the ground, flitting from branch to branch without a care in the world.

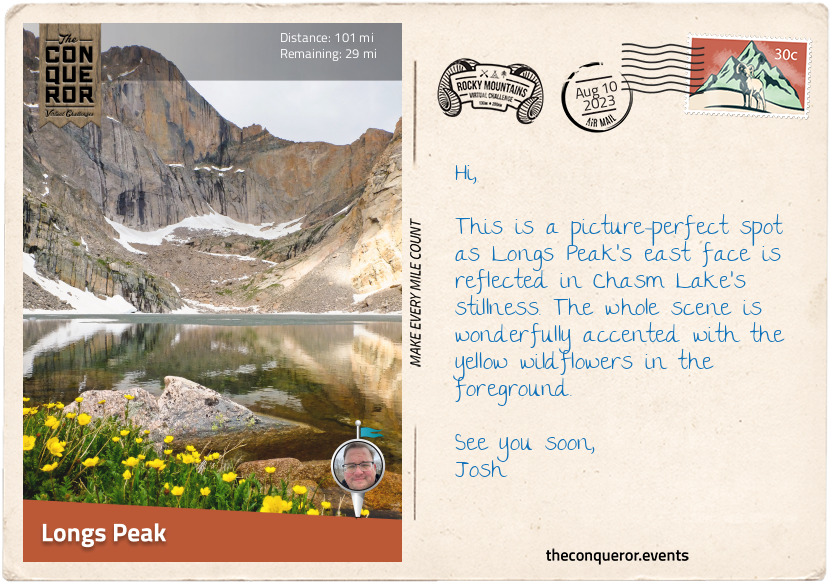

Longs Peak

Longs Peak

Leaving Alberta Falls and swinging past the East Glacier Knob, I took on the toughest climb of this whole journey to Longs Peak. At 14,259ft (4,346m), the peak is the tallest one in the park and the 16th highest Fourteener in the Rocky Mountain range. Needless to say, the hike was rigorous as I climbed 4,465ft (1,361m) in elevation.

On the first stretch of North Longs Peak Trail, I tackled a series of switchbacks and then skirted the base of Half Mountain to Boulder Brook. The well-maintained and quiet trail was lined with bristlecone pine and subalpine fir. The hike was moderate but nothing overly tricky yet.

After a few more switchbacks, I was above the treeline, where the landscape was grassy and rocky. I climbed up the side of Battle Mountain to a junction at Granite Pass and stopped at a small wooden sign giving directions to different trails.

Taking the Keyhole Route, I continued climbing. The maintained trails disappeared, and I climbed into a vast valley of rocks, stepping on them one after the other. Keeping my head up to take in the views proved difficult as rocks of all shapes and sizes threatened to turn my ankle any minute.

The further up I went, the tougher it got, and then came the Keyhole. Massive boulders strewn together in a jumble formed my trail ahead. As I scrambled up, my heart palpitating from the effort, I wondered if I should continue. This was only my halfway point, and the climb got very real. The Keyhole was a long ridge extending from Longs Peak's north with a rock notch at the top. Crossing through the gap felt like entering another realm, but when looking in either direction, it was all rocks and formidable granite peaks.

A good dose of gusty wind hit me as I stepped through the Keyhole. It swiped at my face and body as the wind dared me to quit while trying to knock me off my feet. Seeing a conical building just below, I armed myself with will and stubbornness and climbed down to seek shelter and respite. A plaque on the wall acknowledged Agnes Vaille, who in 1925 was the first woman to ascend the East Face of Longs Peak. Sadly, she died of exposure when she slipped and fell on her descent. Her father always wondered if a shelter may have saved her and, in her honour, built the structure I took cover in.

The next phase of my hike was The Ledges, where I had to navigate a long series of slabbed rock ledges. Although the trail was flat, the heart-stopping drop to the west kept me focused and moving forwards, often using all four limbs to navigate this area.

Having reached The Trough, a short scree-filled gully, I definitely questioned my sensibilities. This trail was not for the faint of heart. I almost didn't dare to look at the views but was pleased to catch a glimpse of a few lakes far in the distance. More scrambling ensued as I climbed 1,000ft (300m) through The Trough, watching out for loose rocks.

And just when I thought it couldn't get any scarier, I reached The Narrows, a stretch of rock barely 3ft (1m) wide hugging a wall 1000ft (300m) high to one side and a clear drop to the other. Slowly inching across it, I stuck closely to the wall, so the wind wouldn't blow me off while also being mindful of where I stepped on the uneven sections.

Once past The Narrows, I was on The Homestretch, a 300ft (90m) climb across steep rock slabs with limited handholds. Again I had to be slow and careful with my movements so I would not slip, and finally, I reached the top. To my surprise, the summit of Longs Peak was flat and as large as a football field. The views were spectacular, with Storm Peak to the northwest, Mount Meeker to the southeast, and Chasm Lake and Peacock Pool below the east face.

I basked in my accomplishment here and remembered the extraordinary people who successfully climbed the peak. The Father of RMNP, Enos Mills, summited it 340 times but was outdone a few decades later by Jim Detterline, whose summit statistics exceeded 420 and more than 1,000 rescues in the area. William Butler celebrated his 85th birthday on top of Longs Peak, making him the oldest person to summit the peak. Lisa Foster summited it 193 times as of December 2022 and is the only female to hold such a great number of ascents.

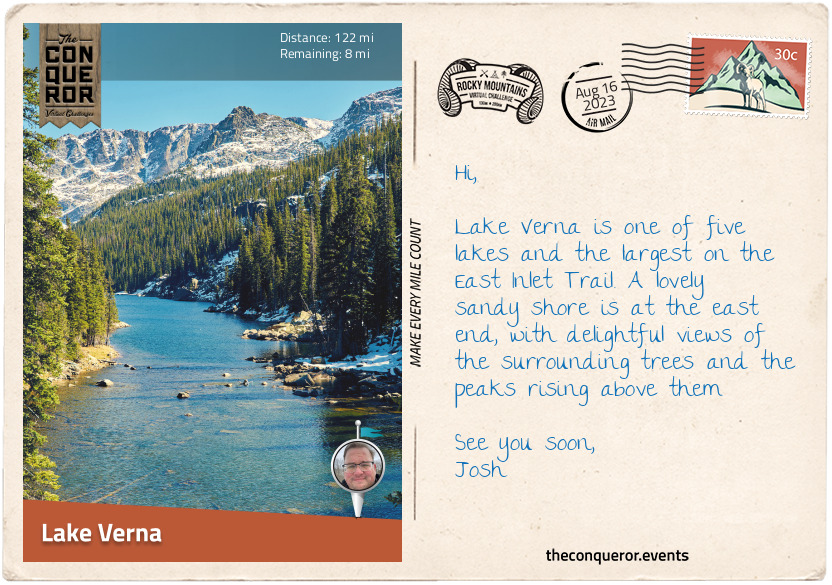

Lake Verna

Lake Verna

Filled with satisfaction after my successful summit of Longs Peak and a good night's rest in my tent, I packed up early in the morning and headed down the mountain. Although the descent was still rocky, it was welcomed. Small clumps of yellow flowers dotted the landscape. When I reached Chasm Junction, I looked back at the park's second-highest peak, Mount Meeker, the smooth east face of Longs Peak called The Diamond and Chasm Lake in the valley below.

I walked through an expansive landscape dotted with rocks and low-lying shrubbery. Crossing Alpine Brook, I entered the woods and peacefully hiked amongst the trees for the next 3mi (5km). From there, I connected to South St Vain Avenue, where I came across St Catherine of Siena Chapel. Also known as the Chapel on the Rock, this pretty church rose like a castle from a large rock. It took twenty years to build it, finally opening in 1936, and while it suffered damage a few times because of natural disasters, today, it is a lovely elaborate stone building with detailed stained-glass windows. In 1999, it was designated a historic site by the local county.

I proceeded south for a couple of miles, then veered west, passing Copeland Lake, a popular location for fishing brook trout. I jumped off the trail for a quick hike to Copeland Falls and then back into the aspens-filled woods. I reached the trail's end at Thunder Lake, ringed by pine trees and the peaks of Pilot Mountain and Tanima Peak.

After the lake, I hiked off the beaten path to the Lake of Many Winds, where I scrambled up to Boulder-Grand Pass. From here, I had wonderful views of the verdant valley below, the lakes I passed by, and all the way to Longs Peak and Mount Meeker. Absorbing the panorama, I took a moment to marvel at the beauty of nature.

From the Pass, I descended 1300ft (400m) to hike East Inlet Trail beside the boulder-filled shoreline of Fourth Lake. The trail was opened in 1913 to access the five lakes east of Grand Lake. The first half of the trail was developed and improved upon many times over the decades, but the second half was left untended. Since I came from the opposite direction, I joined the part of the trail that was not maintained and found I had to climb over many downed trees. While the first three lakes were given names, Fourth Lake and Fifth Lake, which was further behind me, seemed to have missed out on their own unique names.

From Fourth Lake, I walked past Spirit Lake, and a short distance later, I reached Lake Verna. Long and narrow with a sandy shore, Lake Verna was the largest of the East Inlet Lakes. The craggy peaks of Mount Craig and Andrews Peak rose above the surrounding treelines on either side of the lake.

I pulled up at the Lake Verna Campsite and set up for the night. Topping up my water at a nearby stream, I settled down to make a meal and contemplate my upcoming finish.

Grand Lake

Grand Lake

It was great to return to a well-maintained trail at Lake Verna. The hike to the last of the five lakes, Lone Pine Lake, was a mere mile away. There were several camping spots here, making the location quite popular with hikers.

I zig-zagged in and out of the woods and steadily walked downhill alongside East Inlet. The landscape was verdant, and the nearby mountains were covered in lodgepole pine, spruce, and other tree species.

The inlet snaked beside the trail most of the way and into Grand Lake. Two miles (3.2km) before the end of my journey, I took a short side trip to check out Adams Falls, the last waterfall on this route. Named after Jay E. Adams, an early settler in the late 1800s, the waterfall plunged 55ft (17m) down a series of steps through a narrow rock gorge. I had great views from a platform made with locally sourced rocks and an even better view when I climbed down a little further.

Back on the trail, I forged on and completed my journey in the town of Grand Lake. The lake of the same name is the deepest and largest natural lake in Colorado. This cobalt beauty is popular with water sport enthusiasts and families frolicking on its shores. On the lake's west end is a channel that connects it with Shadow Mountain Lake, a high-elevation reservoir.

As I mentioned at the beginning, Grand Lake is the quiet gateway to the national park, and after my adventures hiking up and down mountains, around lakes, through forests, and along rivers, it was an ideal place to finish and take time to rest and recover.

Pondering my favourite places, I realised that as hair-raising as the climb to Longs Peak was, the challenge to get up there had left its mark. Add to that the views from 14,000+ ft (4300m), and I couldn't ask for more. Other highlights were standing on top of the Continental Divide, the views of the three lakes from the summit of Mt Ida, and the beautiful aspen groves with their silvery bark.

Farewell for now, until the next time.

In addition to the medal below, 5 trees will be planted in my name!

The Conqueror Virtual Challenges, its logo and associated images are owned by ACTIONARY LIMITED.

Route Map

Route Map

Finish Certificate

Finish Certificate

Rewards

Rewards